Origins

There are more than 20,000 species of wild bees. Many species are solitary, and many others rear their young in burrows and small colonies, like mason bees and bumblebees. Beekeeping, or apiculture, is concerned with the practical management of the social species of honey bees, which live in large colonies of up to 100,000 individuals. In Europe and America the species universally managed by beekeepers is the Western honey bee (Apis mellifera). This species has several sub-species or regional varieties, such as the Italian bee (Apis mellifera ligustica ), European dark bee (Apis mellifera mellifera), and the Carniolan honey bee (Apis mellifera carnica). In the tropics, other species of social bee are managed for honey production, including Apis cerana.

All of the

Apis mellifera sub-species are capable of inter-breeding and hybridizing. Many bee breeding companies strive to selectively breed and hybridize varieties to produce desirable qualities: disease and parasite resistance, good honey production, swarming behaviour reduction, prolific breeding, and mild disposition. Some of these hybrids are marketed under specific brand names, such as the

Buckfast Bee or

Midnite Bee. The advantages of the initial F1 hybrids produced by these crosses include: hybrid vigor, increased honey productivity, and greater disease resistance. The disadvantage is that in subsequent generations these advantages may fade away and hybrids tend to be very defensive and aggressive.

Wild honey harvesting

Collecting honey from wild bee colonies is one of the most ancient human activities and is still practiced by aboriginal societies in parts of Africa, Asia, Australia, and South America. Some of the earliest evidence of gathering honey from wild colonies is from rock paintings, dating to around 13,000 BCE. Gathering honey from wild bee colonies is usually done by subduing the bees with smoke and breaking open the tree or rocks where the colony is located, often resulting in the physical destruction of the nest location.

Domestication of wild bees

At some point humans began to domesticate wild bees in artificial hives made from hollow logs, wooden boxes, pottery vessels, and woven straw baskets or "skeps". Honeybees were kept in Egypt from antiquity. On the walls of the sun temple of Nyuserre Ini from the 5th Dynasty, before 2422 BCE, workers are depicted blowing smoke into hives as they are removing honeycombs. Inscriptions detailing the production of honey are found on the tomb of Pabasa from the 26th Dynasty (circa 650 BCE), depicting pouring honey in jars and cylindrical hives. Sealed pots of honey were found in the grave goods of Pharaohs such as Tutankhamun.

In prehistoric Greece (Crete and Mycenae), there existed a system of high-status apiculture, as can be concluded from the finds of hives, smoking pots, honey extractors and other beekeeping paraphernalia in Knossos. Beekeeping was considered a highly valued industry controlled by beekeeping overseers — owners of gold rings depicting apiculture scenes rather that religious ones as they have been reinterpreted recently, contra Sir Arthur Evans.

Archaeological finds relating to beekeeping have been discovered at Rehov, a Bronze- and Iron Age archaeological site in the Jordan Valley, Israel. Thirty intact hives, made of straw and unbaked clay, were discovered by archaeologist Amihai Mazar of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in the ruins of the city, dating from about 900 BCE. The hives were found in orderly rows, three high, in a manner that could have accommodated around 100 hives, held more than 1 million bees and had a potential annual yield of 500 kilograms of honey and 70 kilograms of beeswax, according to Mazar, and are evidence that an advanced honey industry existed in ancient Israel 3,000 years ago. Ezra Marcus, an expert from the University of Haifa, said the finding was a glimpse of ancient beekeeping seen in texts and ancient art from the Near East.

In ancient Greece, aspects of the lives of bees and beekeeping are discussed at length by Aristotle. Beekeeping was also documented by the Roman writers Virgil, Gaius Julius Hyginus, Varro, and Columella.

The art of beekeeping appeared in ancient China for a long time and hardly traceable to its origin. In the book "Golden Rules of Business Success" written by Fan Li (or Tao Zhu Gong) during the Spring and Autumn Period there are some parts mentioning the art of beekeeping and the importance of the quality of the wooden box for bee keeping that can affect the quality of its honey.

Study of honey bees

It was not until the 18th century that European natural philosophers undertook the scientific study of bee colonies and began to understand the complex and hidden world of bee biology. Preeminent among these scientific pioneers were Swammerdam, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, Charles Bonnet, and the blind Swiss scientist Francois Huber. Swammerdam and Réaumur were among the first to use a microscope and dissection to understand the internal biology of honey bees. Réaumur was among the first to construct a glass walled observation hive to better observe activities within hives. He observed queens laying eggs in open cells, but still had no idea of how a queen was fertilized; nobody had ever witnessed the mating of a queen and drone and many theories held that queens were "self-fertile," while others believed that a vapor or "miasma" emanating from the drones fertilized queens without direct physical contact. Huber was the first to prove by observation and experiment that queens are physically inseminated by drones outside the confines of hives, usually a great distance away.

Following Réaumur'sBurnens, to make daily observations, conduct careful experiments, and to keep accurate notes over a period of more than twenty years. Huber confirmed that a hive consists of one queen who is the mother of all the female workers and male drones in the colony. He was also the first to confirm that mating with drones takes place outside of hives and that queens are inseminated by a number of successive matings with male drones, high in the air at a great distance from their hive. Together, he and Burnens dissected bees under the microscope and were among the first to describe the ovaries and spermatheca, or sperm store, of queens as well as the penis of male drones. Huber is universally regarded as "the father of modern bee-science" and his "Nouvelles Observations sur Les Abeilles (or "New Observations on Bees") [2]) revealed all the basic scientific truths for the biology and ecology of honeybees.

Invention of the movable comb hive

Early forms of honey collecting entailed the destruction of the entire colony when the honey was harvested. The wild hive was crudely broken into, using smoke to suppress the bees, the honeycombs were torn out and smashed up — along with the eggs, larvae and honey they contained. The liquid honey from the destroyed brood nest was crudely strained through a sieve or basket. This was destructive and unhygienic, but for hunter-gatherer societies this did not matter, since the honey was generally consumed immediately and there were always more wild colonies to exploit. But in settled societies the destruction of the bee colony meant the loss of a valuable resource; this drawback made beekeeping both inefficient and something of a "stop and start" activity. There could be no continuity of production and no possibility of selective breeding, since each bee colony was destroyed at harvest time, along with its precious queen. During the medieval period abbeys and monasteries were centers of beekeeping, since beeswax was highly prized for candles and fermented honey was used to make alcoholic mead in areas of Europe where vines would not grow.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw successive stages of a revolution in beekeeping, which allowed the bees themselves to be preserved when taking the harvest.

Intermediate stages in the transition from the old beekeeping to the new were recorded for example by Thomas Wildman in 1768/1770, who described advances over the destructive old skep-based beekeeping so that the bees no longer had to be killed to harvest the honey.

Wildman for example fixed a parallel array of wooden bars across the top of a straw hive or skep (with a separate straw top to be fixed on later) "so that there are in all seven bars of deal" [in a 10-inch-diameter (250 mm) hive] "to which the bees fix their combs". He also described using such hives in a multi-storey configuration, foreshadowing the modern use of supers: he described adding (at a proper time) successive straw hives below, and eventually removing the ones above when free of brood and filled with honey, so that the bees could be separately preserved at the harvest for a following season. Wildman also described

a further development, using hives with "sliding frames" for the bees to build their comb, foreshadowing more modern uses of movable-comb hives. Wildman's book acknowledged the advances in knowledge of bees previously made by Swammerdam, Maraldi, and de Reaumur—he included a lengthy translation of Reaumur's account of the natural history of bees—and he also described the initiatives of others in designing hives for the preservation of bee-life when taking the harvest, citing in particular reports from Brittany dating from the 1750s, due to Comte de la Bourdonnaye.

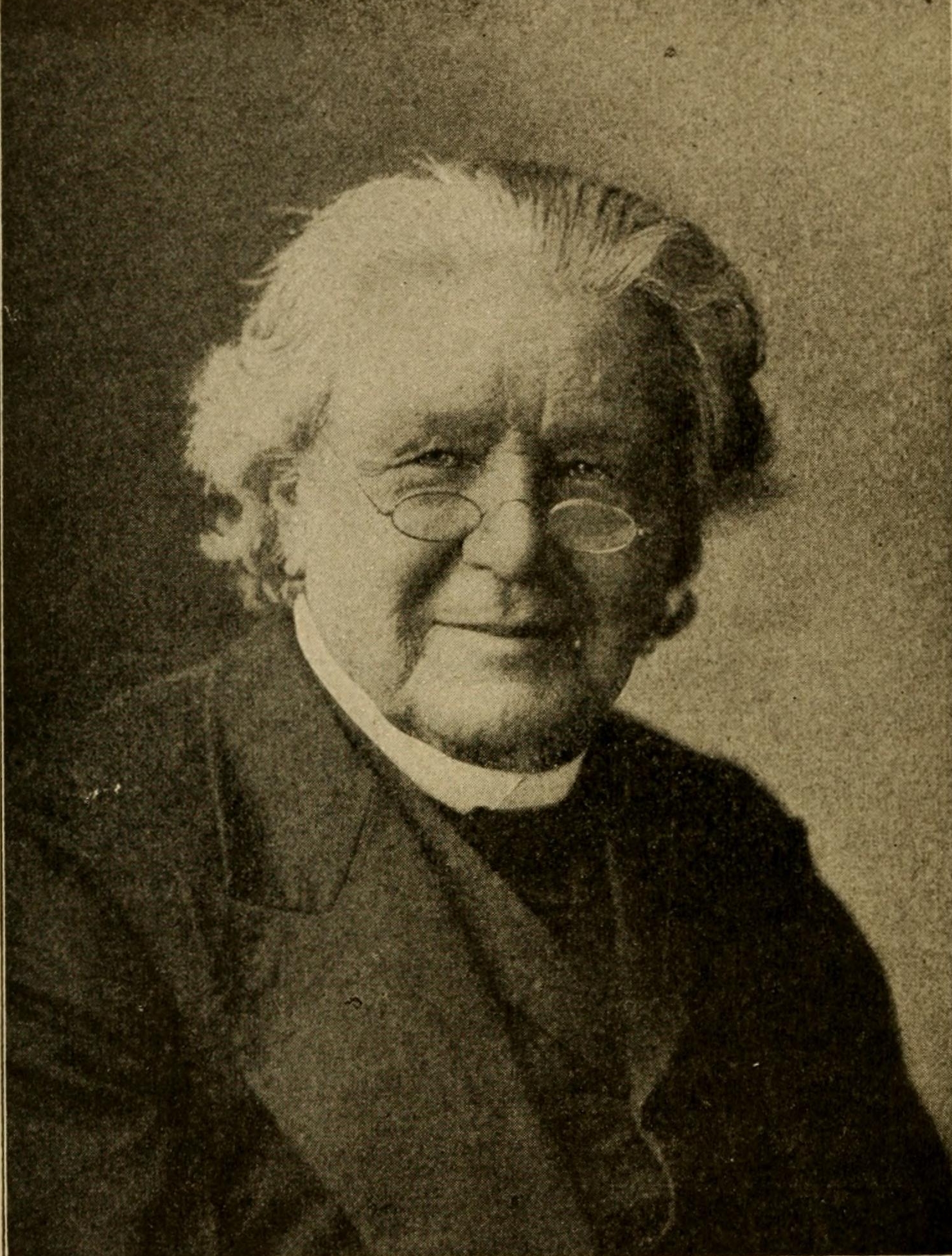

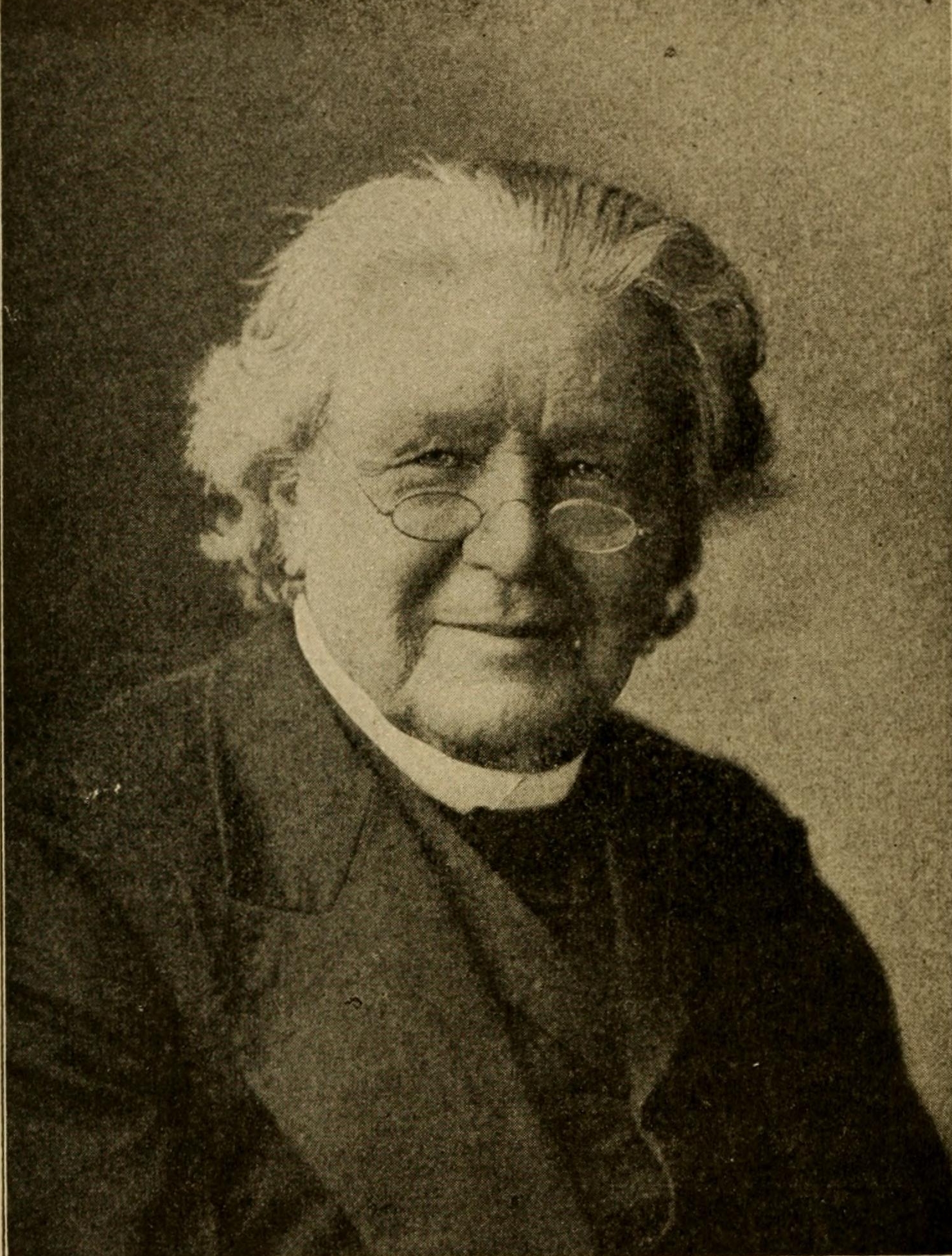

Lorenzo Langstroth (1810-1895)

The 19th Century saw this revolution in beekeeping practice completed through the perfection of the movable comb hive by Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth, a descendant of Yorkshire farmers who emigrated to the United States. Langstroth was the first person to make practical use of Huber's earlier discovery that there was a specific spatial measurement between the wax combs, later called "the bee space", which bees would not block with wax, but kept as a free passage. Having determined this "bee space" (between 5 and 8 mm, or 1/4 to 3/8"), Langstroth then designed a series of wooden frames within a rectangular hive box, carefully maintaining the correct space between successive frames, and found that the bees would build parallel honeycombs in the box without bonding them to each other or to the hive walls. This enables the beekeeper to slide any frame out of the hive for inspection, without harming the bees or the comb, protecting the eggs, larvae and pupae contained within the cells. It also meant that combs containing honey could be gently removed and the honey extracted without destroying the comb. The emptied honey combs could then be returned to the bees intact for refilling. Langstroth's classic book,

The Hive and Honey-bee, published in 1853, described his rediscovery of the bee space and the development of his patent movable comb hive.

The invention and development of the movable-comb-hive fostered the growth of commercial honey production on a large scale in both Europe and the USA.

See also:

Beekeeping in the United States

Evolution of hive designs

Langstroth's design for movable comb hives was seized upon by apiarists and inventors on both sides of the Atlantic and a wide range of moveable comb hives were designed and perfected in England, France, Germany and the United States. Classic designs evolved in each country: Dadant hives and Langstroth hives are still dominant in the USA; in France the De-Layens trough-hive became popular and in the UK a British National Hive became standard as late as the 1930s although in Scotland the smaller Smith hive is still popular. In some Scandinavian countries and in Russia the traditional trough hive persisted until late in the 20th Century and is still kept in some areas. However, the Langstroth and Dadant designs remain ubiquitous in the USA and also in many parts of Europe, though Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France and Italy all have their own national hive designs. Regional variations of hive evolved to reflect the climate, floral productivity and the reproductive characteristics of the various subspecies of native honey bee in each bio-region.The differences in hive dimensions are insignificant in comparison to the common factors in all these hives: they are all square or rectangular; they all use movable wooden frames; they all consist of a floor, brood-box, honey-super, crown-board and roof. Hives have traditionally been constructed of cedar, pine, or cypress wood, but in recent years hives made from injection molded dense polystyrene have become increasingly important.

Hives also use queen excluders between the brood-box and honey supers to keep the queen from laying eggs in cells next to those containing honey intended for consumption. Also, with the advent in the 20th century of mite pests, hive floors are often replaced for part of (or the whole) year with a wire mesh and removable tray.

Pioneers of practical and commercial beekeeping

The 19th Century produced an explosion of innovators and inventors who perfected the design and production of beehives, systems of management and husbandry, stock improvement by selective breeding, honey extraction and marketing. Preeminent among these innovators were:

Jan Dzierżon, was the father of modern apiology and apiculture. All modern beehives are descendants of his design.

L. L. Langstroth, Revered as the "father of American apiculture", no other individual has influenced modern beekeeping practice more than Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth. His classic book

The Hive and Honey-bee was published in 1853.

Moses Quinby, often termed 'the father of commercial beekeeping in the United States', author of

Mysteries of Bee-Keeping Explained.

Amos Root, author of the

A B C of Bee Culture which has been continuously revised and remains in print to this day. Root pioneered the manufacture of hives and the distribution of bee-packages in the United States.

A.J. Cook, author of

The Bee-Keepers' Guide; or Manual of the Apiary, 1876.

Dr. C.C. Miller was one of the first entrepreneurs to actually make a living from apiculture. By 1878 he made beekeeping his sole business activity. His book,

Fifty Years Among the Bees, remains a classic and his influence on bee management persists to this day.

Major Francesco De Hruschka was an Italian military officer who made one crucial invention that catalyzed the commercial honey industry. In 1865 he invented a simple machine for extracting honey from the comb by means of centrifugal force. His original idea was simply to support combs in a metal framework and then spin them around within a container to collect honey as it was thrown out by centrifugal force. This meant that honeycombs could be returned to a hive undamaged but empty, saving the bees a vast amount of work, time, and materials. This single invention greatly improved the efficiency of honey harvesting and catalysed the modern honey industry.

Walter T. Kelley was an American pioneer of modern beekeeping in the early and mid 20th century. He greatly improved upon beekeeping equipment and clothing and went on to manufacture these items as well as other equipment. His company sold via catalog worldwide and his book,

How to Keep Bees & Sell Honey, an introductory book of apiculture and marketing, allowed for a boom in beekeeping following World War II.

In the UK practical beekeeping was led in the early 20th century by a few men, pre-eminently

Brother Adam and his Buckfast bee and

R.O.B. Manley, author of many titles, including 'Honey Production In The British Isles' and inventor of the Manley frame, still universally popular in the UK.

Other notable British pioneers include William Herrod-Hempsall and Gale.

This article from Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beekeeping#Domestication_of_wild_bees